Defiance

A conversation with Loubna Mrie

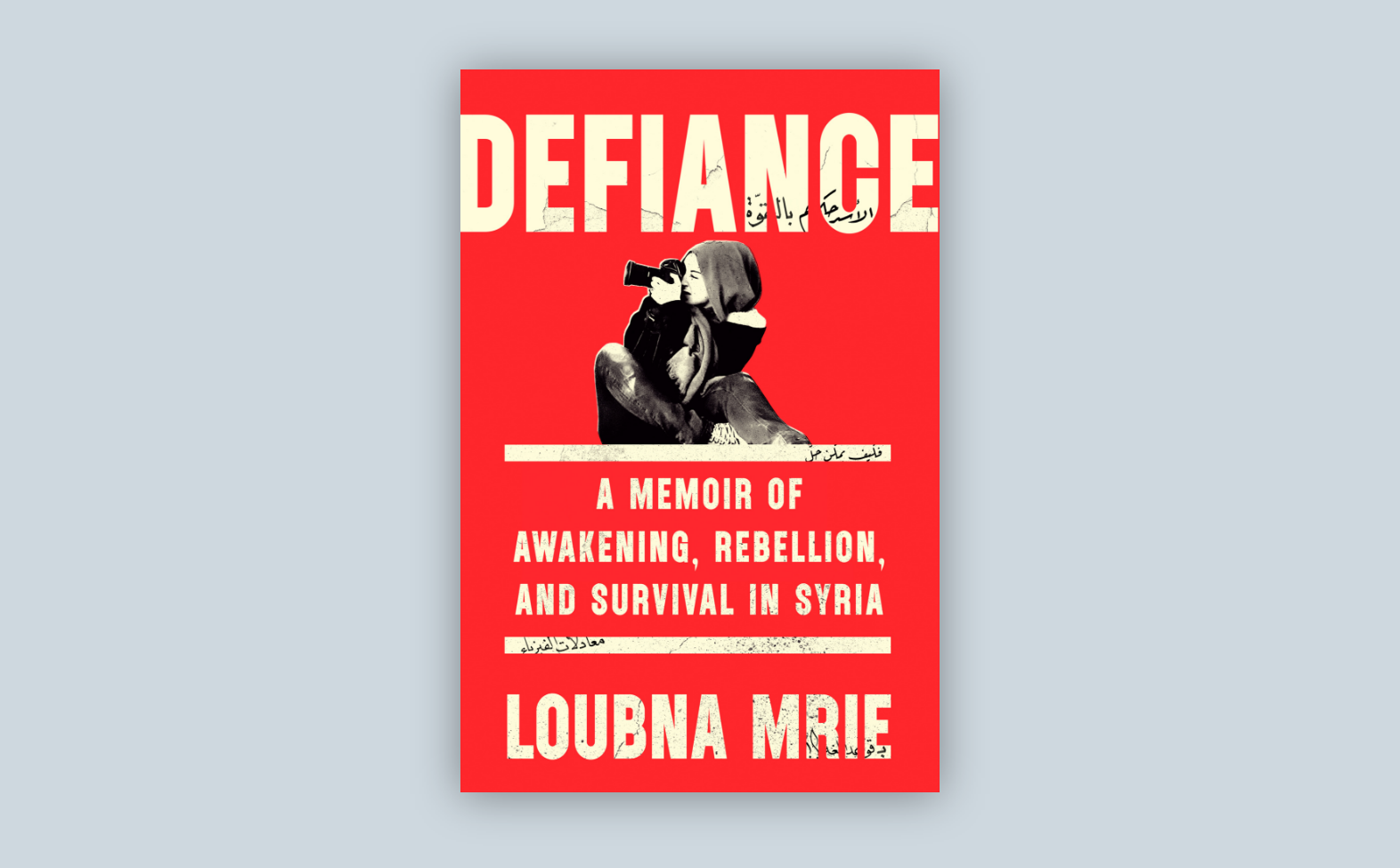

Loubna Mrie’s book 'Defiance: A Memoir of Awakening, Rebellion, and Survival in Syria’ will be published later this month. Syria in Transition provides a mini review and speaks with the author about the mood in the Alawite community, hurdles to nationwide reconciliation, the state of media and reporting, and more.

In Defiance, Loubna Mrie, now 34, tells an autobiographical story that is inseparable from the Syrian revolution itself. She is the daughter of Jawdat Mrie, who rose through the Syrian security apparatus to become security chief to Basil al-Assad and was implicated in the assassination of a dissident abroad, before later turning his attention to a small business empire. Though he never attended university, he was commonly known as ‘Doctor Jawdat’. Mrie grows up in the orbit of this patriarch, who is revered and feared. She writes about life inside a totalitarian system and a totalitarian family, from the perspective of a child whose loyalty was once absolute. Her mother, who initially saw her marriage to Jawdat as a privilege, was quickly disabused of that belief by his violence. Trapped by overlapping personal and structural constraints, she nonetheless tries — quietly and imperfectly — to loosen the grip of family determinism on her daughters.

When the revolution begins, Loubna is twenty. A moral curiosity, something like an internal compass, draws her beyond usual boundaries. She joins protests, marches alongside Sunnis and Christians and gradually aligns herself with the victims of a regime whose brutality had until then been largely invisible to her. As a young woman, as an Alawite, and as a member of a powerful family she openly disdains the regime, and becomes known beyond Syria. Her defiance provokes her father. She is disowned. Fearing for her life, she flees to Turkey in 2013. Jawdat attempts to lure her back, and ultimately has her mother killed. Mrie continues working as a journalist, documenting the battle for Aleppo and life in rebel-held areas. With the rise of the Islamic State, the tentative vision of a free Syria collapses. Friends are murdered. Her partner, Peter Kassig, is abducted and executed by the jihadists. A journalism fellowship in the United States intended to last six weeks becomes a permanent exile.

Despite its violent and tragic material, the book avoids theatricality. There is even humour. Mrie writes about unhealthy coping mechanisms and about the naivety of the secular opposition so warmly embraced in the West. She reflects on how she deliberately avoided documenting the uglier aspects of the revolution — arbitrary violence, warlordism, the rise of Islamist factions — partly to preserve, for herself, a version of Syria that might still justify the sacrifices already made. Defiance captures both the spell of revolutionary momentum and the hangover of a revolution stolen by many thieves. Above all, it asserts the vital need for an inner moral orientation, albeit often obscured. It is this that exposes antagonism as man-made and therefore reversible - a crucial insight for a revolution that, in many ways, is still ongoing.

In your book, you write: “It isn’t just the government that is oppressive, I realise; oppression is deeply embedded in my own family. 'Good' women, like all marginalised Syrians, must follow the rules and never question or challenge the powers that be. In return for total submission, we are led to believe that these authorities — fathers, husbands, dictators — will guarantee our safety.”

This recalls what Raed Fares once described as the “little Assad” the regime planted inside every Syrian. How can these deeply internalised patterns of obedience and submission be broken?

Mrie: I don’t think these patterns can be broken unless we first understand their roots. For decades in Syria, blind loyalty was rewarded. Justifying the leader’s mistakes and endlessly pledging allegiance were how you proved yourself a “good” citizen. What makes this pattern especially dangerous is that it doesn’t exist only in political life. It begins inside the home. The father figure is treated as the one who knows what’s best for you, and any form of pushback is considered betrayal. Whether in politics, at home, or at school, speaking your mind and questioning authority become associated with treason. You are taught that those in power oppress you for your own protection, and that obedience is the price of safety.

To change these patterns, we have to stop equating safety with obedience, and dissent with punishment.

But the patterns you describe also seem to leave very little inner space — emotionally or intellectually — even to begin examining their roots. That feels like a catch-22: you need awareness to break the cycle, but the cycle itself blocks that awareness. How can people begin to move through this? In your own case, it seems that compassion came before analysis.

Mrie: The government could play an important role here by letting people experience that critical engagement in political life does not invite punishment. Unfortunately, that shift is not being encouraged. Syrians still associate politics with danger. They feel that if you talk about politics, you end up being punished.

Think about the journalists with roots in the opposition who framed the massacres on the coast as fake or exaggerated. The language is disturbingly familiar from the Assad era. What is especially frightening is that the government rewards these voices. Loyalty remains the main gateway to access, privilege, and power.

When it comes to transitional justice, narratives of victimhood seem overwhelming on all sides. That feels like a recipe for polarisation, given that reconciliation requires grappling with being both victims and perpetrators. How do you see this dynamic within the Alawite community?

Mrie: Many still dismiss the Caesar photos as fabrications and refuse to acknowledge the use of barrel bombs or chemical weapons. Atrocities that cannot be denied because they were witnessed directly are often relativised: violence committed by rebels is framed as equal to, or worse than that of the regime. The dominant narrative becomes one of self-defence: “we were protecting our homeland.” This propaganda runs so deep that it becomes difficult to distinguish between conscious denial, internalised belief and psychological self-protection.

I believe that anyone who played a role in the regime’s security apparatus or army must be held accountable. This is why transitional justice matters so much, including for Alawites themselves. Without accountability, Alawites will remain exposed to collective punishment. The massacres in March were also the consequence of the new government’s failure to address transitional justice early on — even symbolically, even through public communication. That vacuum allowed rage to fester and revenge to appear legitimate to some.

Accountability, of course, must go hand in hand with reconciliation — and reconciliation is only possible within a state governed by law that protects human rights and opens political space to everyone.

In your book, you describe how, as a journalist, you buried stories of arbitrary violence and crimes committed by rebels — both psychologically and through your camera — so that the Syria you documented could still justify your losses: “A promising new version of Syria, one that can justify my staggering losses.” Do you see a similar pattern at work today?

Mrie: Yes — because at the time, I needed the story to make sense of my losses. Like many others, I clung to the hope that the future would be brighter, that it would somehow justify what had been taken. That’s why I understand how this logic repeats itself — and why it feels so familiar now.

Over time, the longing for a Syria many believed they would never see again began to overpower political judgment. Al-Sharaa came to embody the possibility of belonging and return. This shift cannot be separated from years of witnessing Assad’s crimes — and by witnessing, I don’t mean only those physically present. Millions experienced this violence through screens, from exile, until brutality became ambient. The moral bar for what counted as unacceptable violence has collapsed. Perhaps that’s how we arrived at a moment where anything less than Assad seemed tolerable.

Does this dynamic also apply to foreigners?

Mrie: Of course. There is understandable excitement that Syria is now open to the West — that one can go to Damascus and tour the Presidential Palace. I understand that access matters for careers of journalists and experts. But access also creates responsibility. When journalists or experts gain and protect their access by turning a blind eye to human rights violations or authoritarianism, they do Syrians no service.

In your book you recall an episode of 2013, writing: “I just want to be normal, even though I don’t know what normal truly means.” What is your relationship to “normality” today?

Mrie: I think I stopped trying to be normal. In the last chapters of the book, I describe how, when I first learned about seasonal depression, part of me almost longed for it — to be sad because of yellow leaves and drizzle, rather than loss and displacement. At twenty-three, when I immigrated to New York, I felt cursed for carrying so much grief. Now, as I approach thirty-five, my relationship to normality has shifted. I’ve learned to accept my wounds instead of trying to hide or outgrow them. I no longer measure myself against an idea of “normal” that was never designed to hold a life like mine.

In the epilogue, I write about letting go of the idea that belonging has to be tied to a single place. Over time, I’ve learned that stability — and even a sense of home — can come from within.

With the onset of the Arab Spring, your book shifts from past tense to present tense. Why did you make that choice?

Mrie: It was a structural decision as much as an emotional one. The early sections are written in the past tense to create distance from childhood. Those events are filtered through memory; they are already interpreted and contained.

When the Arab Spring begins, the narrative moves into the present tense because I am no longer reflecting — I am moving through events as they unfold. The present tense brings the reader into immediacy, into uncertainty, into a moment where perception is still forming rather than resolved. Craft-wise, it signals a shift from remembered life to lived life, from retrospection to witnessing.

Now that some time has passed since you finished the book — and in light of rapidly unfolding events in Syria — are there parts of the story, or of Syria, that have moved for you from witnessing into a more settled understanding?

Mrie: Exile doesn’t have to be geographical. You can be exiled within your own country, your community, even your family. But in one form or another, becoming your authentic self sometimes requires exile.