The Baath Party: a sadistic reading

26. January 2026

A pair of Baathist memoirs, read against de Sade’s Justine, reveal a politics that rewards brutality and betrayal while clinging to the language of virtue.

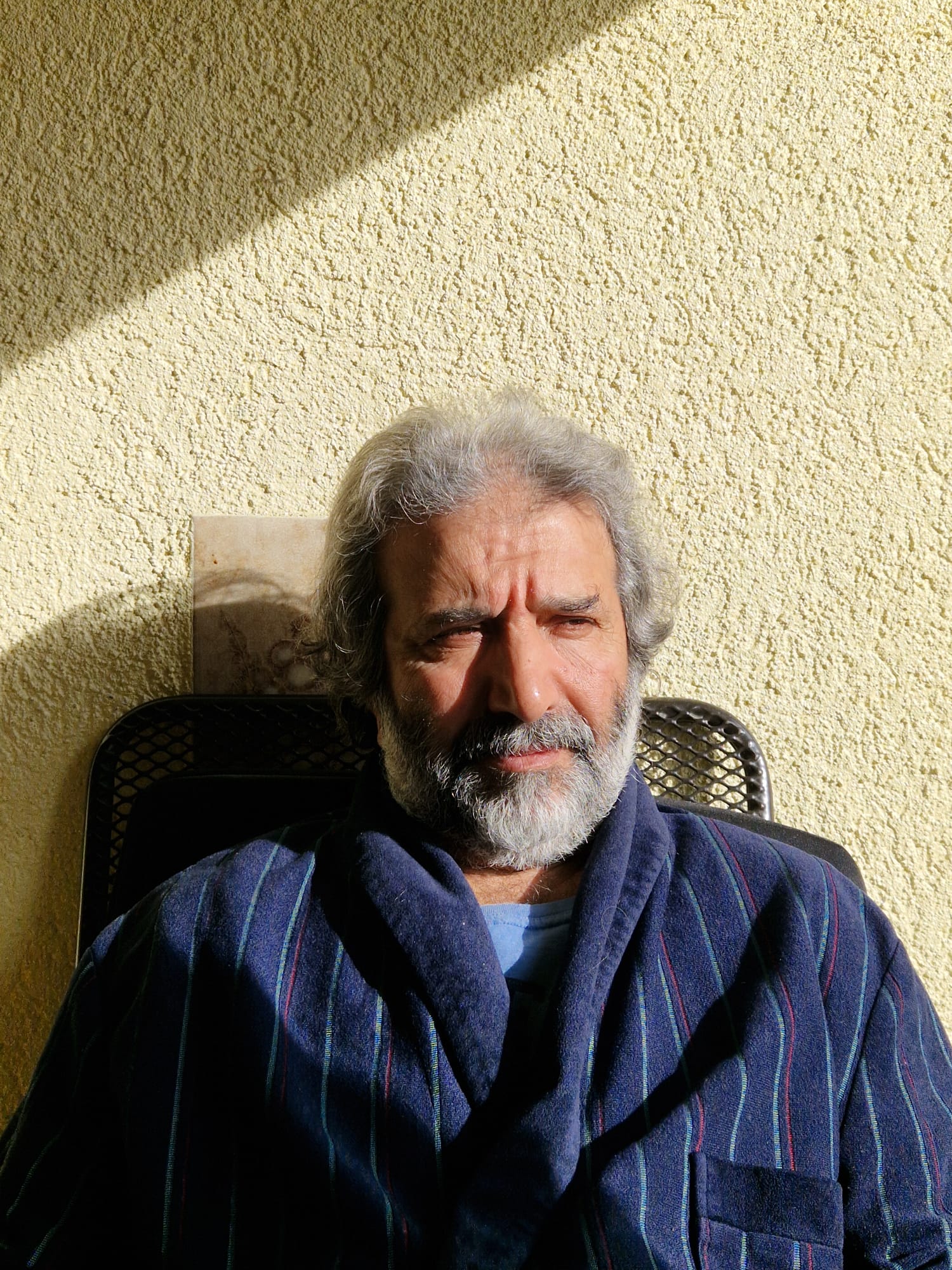

By a curious coincidence, two books about the Arab Socialist Baath Party reached me last week. The first concerns a son of the Lebanese city of Tripoli, Abdulmajid al-Rafai, a historic leader of the Baath Party (the Iraqi-aligned wing in Lebanon). The second is about Muhammad Rashad al-Sheikh Radi, a native of Najaf in Iraq, a “member of the Iraqi Regional Command” and a “reserve member of the National Command of the Baath Party” – titles that, in the Syrian context, point clearly to the Iraqi wing of the Baath.

The book They Pass, It Remains: Pages from the Life of Dr Abd al-Majid al-Tayyib al-Rafai, by Dr Khaled Breish (Arab Institute for Research and Publishing), notes that al-Rafai came from a prominent religious family in Tripoli. His decision to join a “secular party” was therefore regarded as strange, given that he was “the son of the Rafai family, standard-bearers of Islam, deeply rooted in the scholarly, religious and cultural history of Tripoli, which has given the ummah a distinguished group of jurists, scholars, muftis and judges”.

Sheikh Radi, for his part, writes in The Baath as I Knew It: The Memoirs of Muhammad Rashad al-Sheikh Radi (Dar al-Hikma, London) that he too belonged to a religious family from Najaf, descending from Ayatollah Sheikh Radi, a jurist considered among the leading teachers of the Hawza and one of the Shi’ia religious authorities of the time.

According to Breish’s account, al-Rafai was shaped by the great political struggles of the Arab world, above all the Nakba of 1948 and the subsequent rise of Arab nationalism during the era of Nasser and the Baath. This mirrors what Sheikh Radi says about the context of his own affiliation with the party, forged amid the unificationist slogans of the 1950s. He adds, however, another decisive factor: his confrontation with the Communists after the 1958 revolution, who, as he puts it, “seized control of most of the levers of the state”.

The Baath as I Knew It, the first volume of Sheikh Radi’s memoirs, carries an oddly optimistic subtitle: Nothing Makes Us Lose Hope. Like many memoirs by former Baathists, it contains criticisms of the party. Yet Sheikh Radi differs from almost all others – as the editor points out – in that he remained, “without exception”, insistent on his pride in the Arab Socialist Baath Party, with the later, telling addition of a qualifier: “the leftist wing”.

Although the book is formally a political autobiography, I found no more illuminating analogy for it than the Marquis de Sade’s Justine. In that novel, Sade dismantles the social, religious, moral and political foundations of nineteenth-century France through the story of two sisters who lose their family and fortune. One chooses the path of virtue, only to suffer a succession of almost unimaginable calamities; the other ascends socially through vice.

Sheikh Radi clings to the virtue he calls “the principles of the party”. His first major rupture comes in 1964 with what he describes as the “right-wing leadership” of Saddam Hussein and Ahmad Hasan al-Bakr, sparked by an episode in which the latter escaped from his jailers. Radi and a group of comrades then split from the Iraqi party on ostensibly “leftist” grounds, while at the same time supporting the “leftist coup” within the Baath that took place in Syria in 1966. When the Baathist coup led by al-Bakr and Hussein succeeded in Iraq in 1968, Radi was arrested and then released, only to rejoin the party while insisting on his attachment to its “principles” and to his earlier split. This eventually drove him to flee to Syria.

From the moment he arrives in Damascus, a series of ironies begins to undermine his claim to “leftist principles”. He and his companions are plunged into the fierce new struggle between the faction led by Salah Jadid and the then minister of defence, Hafez al-Assad. One of the Iraqi comrades, Sidqi Abu Tbeikh, quickly returns home – and leaves party politics altogether – because he is “no longer convinced that the party would, in its trajectory, become a democratic organisation or a model for leading the ummah”. Sheikh Radi, by contrast, finds a justification for distancing himself from Jadid’s camp and aligning with Assad. In Iraq, he had denounced al-Bakr and Saddam’s “correct reading” of the international balance of power as collaboration with foreign interests. In Syria, however, Assad’s similar stance – exemplified by his refusal to provide air support to the Palestinian resistance in Jordan in 1969 – becomes, in Radi’s telling, a realistic assessment of those same balances.

In a gesture reminiscent of Justine, though without its bleak coherence, Sheikh Radi remains verbally committed to the virtue of being a “left-wing Baathist”, despite the absence of any meaningful difference between the regimes in Iraq and Syria, or between “right” and “left”. This insistence persists even as he himself is subjected to grave ordeals: the collusion of Baath officials in Syria with Saddam Hussein’s faction to facilitate his rise to power; the handing over of names and addresses of Iraqi “leftist” dissidents; and personal exposure to conspiracies that culminate in a bloody conflict between leaders of the Iraqi National and Regional Commands in Damascus. One of them is assassinated, Sheikh Radi is accused of the murder, and when the real killer – backed by Rifat al-Assad – is exposed, he is nevertheless kept in his position.

The memoir recounts dangerous episodes in which senior party leaders are shown to be enmeshed in lethal games, loyalties shifting between Iraq and Syria, military commanders and security services, with spies, traitors and killers rewarded while they eliminate one another. After all this, Sheikh Radi still clings to the idea of the party’s virtue, presenting it as a “saviour from misguidance”. The catastrophic failures, he argues, stem from the party having been “emptied of its effective role in managing the state”, which led – speaking here of Syria – to “the regime’s horrific collapse, as Damascus fell from being a bastion of Arabism and the wellspring of Arab nationalism into a petty state ruled by those internationally designated as terrorists”.

Al-Rafai’s experience, nevertheless, demands a reading of its own. His Baathist affiliation placed him at the heart of Tripoli’s political and social transformations, but it also, combined with his allegiance to the Iraqi wing, exposed him to grave danger from the Syrian regime and its allies who dominated Lebanon. According to the book, assassinations claimed close comrades around him, such as the lawyer Tahsin al-Atrash and the thinker Abd al-Wahhab al-Kayyali, “while others were thrown into the depths of prisons in the corridors of the Syrian regime, where they were subjected to the most degrading insults and the vilest forms of repression and torture”.