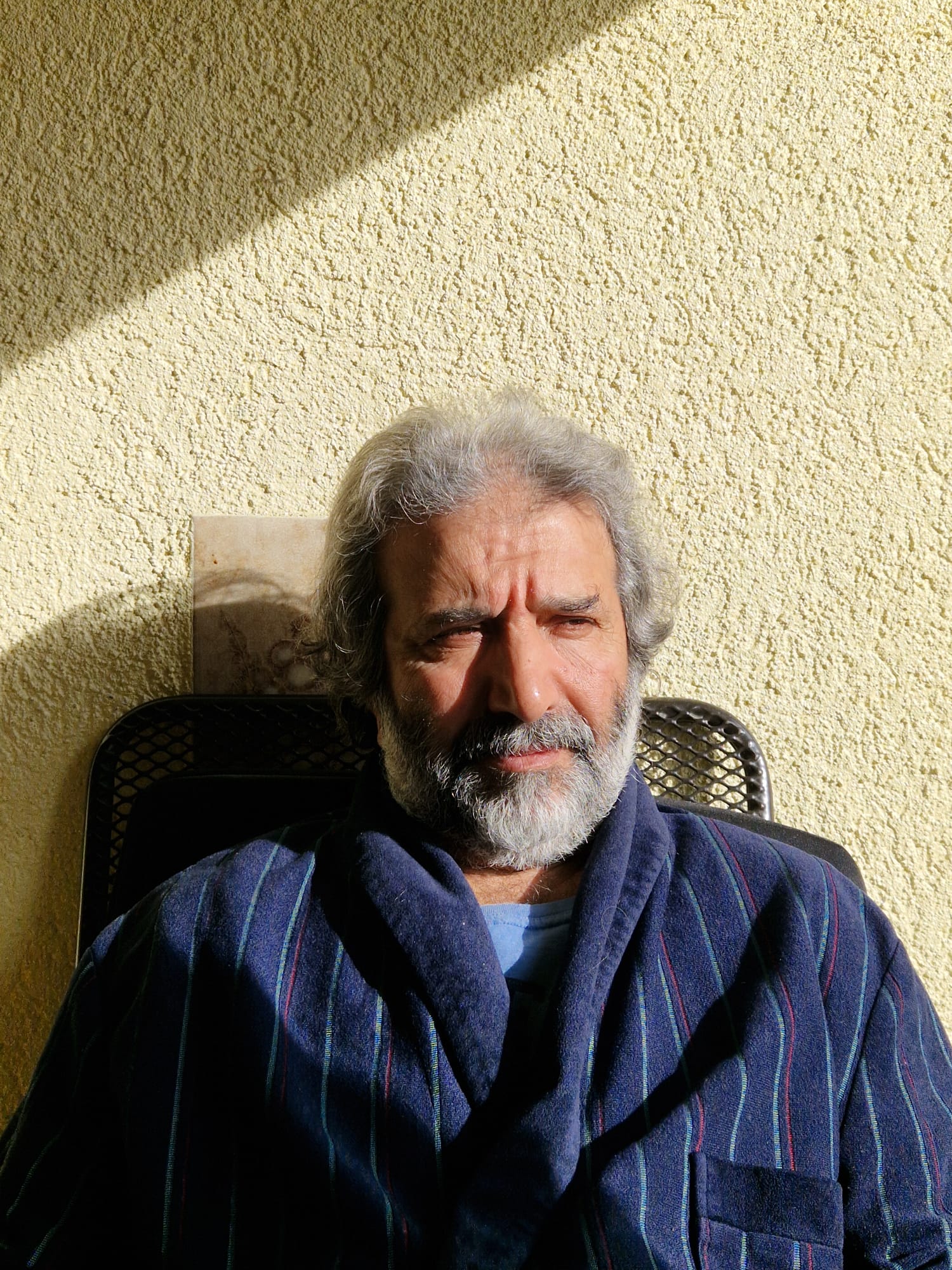

How Fawwaz Haddad’s novels expose the Syrian condition

7. February 2026

Fawwaz Haddad is a novelist who has traced the Syrian experience over the past fifty years. Long considered seditious under the former regime, his novels examine how political domination reshapes thought, culture, and moral judgment. In doing so, he has become one of the clearest literary voices of his generation.

Since the publication of his first novel, Mosaic (1991), Fawwaz Haddad has carved out a distinctive trajectory within contemporary Syrian fiction. It preoccupied itself with questions of power, the position of the intellectual within structures of despotism, and the fraught relationship between the individual, history, and politics. This project reached its most concentrated and intense phase with the outbreak of the Syrian revolution (2011–2024), when Haddad’s novels ceased to function as acts of documentation and instead became instruments of exposure: imaginative spaces capable of penetrating what the social sciences could not fully grasp.

From the novel of the moment to existential questions

Having completed six pivotal novels on the Syrian revolution and on half a century of totalitarian rule, Haddad considers this phase of his literary journey closed. These works – beginning with The Syrians: The Enemy (2014) and culminating in The Suspicious Novelist (2025) – were not, at their core, reactive responses to unfolding events. Rather, they constituted a sustained engagement with the Syrian condition at a time of crisis, where the police state slowly collapsed amid social devastation, and ethical and human values steadily eroding.

The phase that follows, as Haddad conceives it, will not be a mechanical continuation of this path, but a turn towards deeper questions: Who are we? What do we want? And how can a shattered society, having lost its sense of direction, recover a moral and existential compass? Here the novel relinquishes the function of direct political dissection and turns instead to narrating the story of the Syrian individual worn down by the machinery of repression, and by starvation, destruction, and displacement.

Knowledge as a condition of seeing

Haddad’s novels are often described as encyclopaedic, dense with historical, religious, political, cultural, and artistic references. Haddad himself resists the label. What he has accumulated, he insists, is not knowledge as an end in itself, but knowledge as an instrument – an enabling condition for entering the worlds he writes about.

In his work, knowledge is the product of long accumulation, research, and contemplation, but it only comes alive through imagination: that elusive faculty which allows the novelist to penetrate the deeper layers of reality, in all their political, social, and human dimensions, and to disclose what resists rational comprehension or documentary capture. For this reason, Haddad’s fiction is less concerned with delivering ready-made insights than with dismantling the hidden structures of power and society.

Damascus as cultural memory

Damascus occupies a central and enduring place in Haddad’s fictional universe. The old quarters of the city – its alleyways, streets, cafés – are charged symbolic spaces saturated with memory, history, and contradiction. By contrast, Haddad approaches “modern” Damascus with visible reserve, seeing it as an alienating environment, deprived of intimacy and human connection, and marked by a superficial modernity that never fully took social root.

Accordingly, his narratives often gravitate towards what might be called coercive public spaces: prisons, hospitals, detention centres, cafés, cinemas – places where people gather by compulsion or necessity. This spatial logic mirrors Haddad’s vision of Syrian society under a totalitarian state that has since collapsed, but whose imprint endures.

Erasure and cultural authority

Keeping Haddad’s novels from the Syrian reading public was no accident. Official censorship played an obvious role, given the boldness of his critique of power. More insidious, as Haddad himself has argued, was the role of what he terms “cultural authority”: networks of intellectuals who managed the cultural scene, monopolised platforms and events, and expanded the logic of exclusion to encompass both those inside the country and those in exile.

These figures, who proclaimed the values of modernity and progressivism, exercised a parallel form of repression, working to discredit literary voices by accusing them of sectarianism, reactionary thinking, or even terrorism. In Haddad’s fiction, they reappear as narrative material: embodiments of the complicity between culture and despotism.

Black humour

Black humour occupies a central place in Haddad’s work, functioning as a profound mechanism of exposure. It lays bare the grotesque disjunction between ideological rhetoric and the brutal practices it conceals and legitimises. This is not humour as relief, but as attack: a means of unmasking the psychology of the executioner, his counterfeit sanctity, and the underlying banality of repression when it cloaks itself in grand slogans.

Haddad’s narrative techniques emerge organically from the nature of the world he depicts. He draws flexibly on whatever tools are available – traditional or contemporary – without fetishising rupture or privileging the “modern” over the “classical” except insofar as the text itself demands it. Irony, polyphony, the dismantling of authoritarian discourse, and the interweaving of temporal layers coexist without technical exhibitionism. Experimentation here is the inevitable response to a distorted reality that can only be approached through supple, adaptive forms capable of registering both its cruelty and its absurdity.

In this sense, black humour in Haddad’s novels becomes a double practice: epistemological and aesthetic at once. It deepens condemnation rather than easing pain, confronting the reader with a terrifying black comedy that exposes the collapse of the human being within systems of violence, without granting brutality the comfort of aesthetic distance.

The intellectual as a revelatory figure

Haddad’s sustained focus on the figure of the intellectual is anything but incidental. In his novels, the intellectual serves as the most sensitive register of shifts in power and society, a prism through which opportunism, pragmatism, resistance, complicity, and defeat are refracted.

With the ascent of military rule, the intellectual is severed from the centre of decision-making and forced into a redefined role: either to join power and rationalise it, or to adopt a critical, oppositional stance. This plurality of possible positions is what lends the intellectual figure its dramatic and revelatory force within Haddad’s broader project.

Absent criticism

The recurrence of figures such as “the Engineer” in The Syrians: The Enemy, “Khaled” in The Poet and the Collector of Margins, or “Shakib” in The Suspicious Novelist – each appearing in multiple guises – shows a deliberate engagement with a single authoritarian type that changes masks while remaining constant in essence. These characters compete in repression, invent ever-new proofs of loyalty, and expose the internal rivalries of the regime’s own apparatus.

Haddad also points to the retreat of serious literary criticism as a dangerous vacuum. In its absence, the novel has been left to individual whims amplified by social media, and to responses often lacking depth or critical competence, or to the verdicts of politicised prize committees. Major novels, he notes, are rarely popular; yet they often constitute decisive moments in the evolution of art and thought. What is needed, therefore, is a specialised critical discourse capable of reading such works and presenting them as human and intellectual endeavours, not just consumable products.

In this light, Fawwaz Haddad’s writing on the Syrian revolution can be understood as a long process of exposure brought to its climax. Taken as a whole, his novelistic project stands as one of the most serious and profound attempts to understand the Syrian individual within structures of despotism, and as a significant contribution to the contemporary art of the novel.